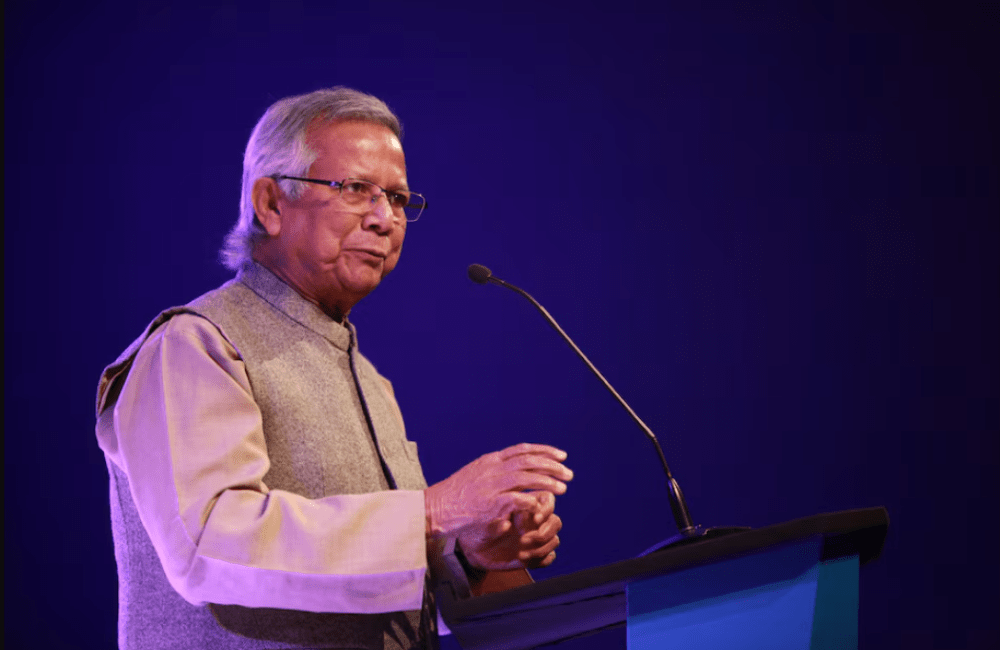

When Muhammad Yunus stepped into leadership as head of Bangladesh’s interim government in mid-2024, the nation was emerging from a long and painful chapter. The collapse of Sheikh Hasina’s 15-year rule—marred by allegations of authoritarianism, mass detentions and deadly crackdowns—left a vacuum and a fractured society. Yunus’s appointment raised hopes for renewal, accountability and long-overdue reform. Nearly a year on, how is he measuring up?

From the outset, Yunus took steps to signal a different kind of leadership. Within days of assuming office, he visited victims of political violence at Dhaka Medical College Hospital, paid respects to families of the deceased and stood in solidarity with communities affected by unrest. These symbolic acts of outreach offered a sharp contrast to the previous government’s approach to dissent and unrest.

On 25 August 2024, Yunus delivered his first address to the nation, outlining an ambitious plan to reform the foundations of governance. He pledged to overhaul Bangladesh’s electoral system, improve the judiciary, modernize the police and revamp public administration. He also emphasized reforming the economy, healthcare and education—areas where systemic weaknesses had long hindered progress.

In September, his administration announced the formation of six national commissions tasked with turning these reform goals into tangible outcomes. The commissions are aimed at institutionalizing good governance, curbing corruption and moving the country away from the centralized, opaque practices that had defined the previous era.

Another key aspect of Yunus’s domestic policy has been a firm commitment to transitional justice. He has pledged to investigate the human rights abuses of the past regime, claiming that many people were killed and 3,500 forcibly disappeared during Hasina’s tenure. To aid victims’ families and support the healing process, his government established the July Shaheed Smrity Foundation in September 2024, backed by a substantial one billion taka fund from the relief budget.

Security has remained a major challenge. In February 2025, following violent unrest linked to the controversial demolition of Dhanmondi 32, Yunus’s government launched “Operation Devil Hunt” to restore order. On its first day, more than 1,300 arrests were made. While firm action was necessary to stabilize the situation, the interim government has maintained that it remains committed to the rule of law and due process.

Yet one of the most pressing questions facing the interim government is: how long will it stay? While opposition parties have demanded fresh elections, Yunus’s legal adviser stated that the government would remain in place “as long as necessary.” It’s a phrase that may cause unease among those who have lived through decades of political stagnation—but also reflects the delicate balance required to stabilize institutions before handing back power.

Despite the complexity of the moment, there is no denying that Yunus has brought a different tone and vision to Bangladeshi governance. His outreach, reform agenda and calls for accountability suggest a genuine effort to correct the injustices of the past. What remains to be seen is whether this vision can be fully realized—and whether it will ultimately lead to a credible, democratic transition.

Bangladesh now stands at a historic inflection point. If Yunus stays true to his promises and delivers on the groundwork he’s laid, his interim government could become a turning point for a nation long in need of healing and reform.